Russia’s Response to U.S. Aid: Shrugs, Disinformation and Warnings of Nuclear War

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — Russia’s reaction to the new infusion of U.S. aid for Ukraine has ranged from shrugs to fury, from warnings of nuclear […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE – Conspiracy theories may have been around since humans began telling stories but today, the volume and spread of such theories is amplified by technology including social media and artificial intelligence. The dangers of conspiracy theories may also be spreading as large segments of populations embrace ideas and stories that have no basis in fact and in the worst cases, can lead some people to consider violence against phantom enemies.

Last week, The Cipher Brief brought together CIA veterans and a journalist who has studied the impact of conspiracy theories for a wide-ranging conversation about the phenomenon, its history, and the risks it may pose to the nation.

All three agreed that as colorful as these theories can be, they can constitute a notable national security threat. “There’s a huge narrative in the country that there’s a deep state and there are people who truly believe it and are actually sometimes willing to commit violence because they believe it so strongly – when it was never true,” said John Sipher, a three-decade veteran of the CIA.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “conspiracy theory” as “a belief that some secret but influential organization is responsible for an event or phenomenon.” That, as our special panel suggested, only begins to tell the story.

THE CONTEXT

THE BRIEFING

The Cipher Brief asked experienced experts in the field to assess and debunk the threats posed by conspiracy theorists.

John Sipher worked for the CIA’s clandestine service for 28 years. He is now a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and a co-founder of Spycraft Entertainment. John served multiple overseas tours as Chief of Station and Deputy Chief of Station in Europe, Asia, and in high-threat environments. He is the recipient of CIA’s Distinguished Career Intelligence Medal.

Jerry O’Shea worked as an operations officer in the CIA for over three decades. He served in Europe, Africa, South Asia, and in the Middle East, as well as in numerous war zones. He is a four-time Chief of Station running some of CIA’s largest and most critical missions abroad.

Adam Davidson is a writer for The New Yorker and author of The Passion Economy. He is co-founder of NPR’s Planet Money and was economics writer and columnist for The New York Times Magazine. He was Middle East Correspondent for the public radio show, Marketplace, and spent a year in Baghdad, Iraq. He has covered many international crises, including the 2004 Tsunami in Indonesia and the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. He has worked on many TV shows and films, including as Adam McKay’s advisor for The Big Short.

This excerpt of the full briefing has been edited for length and clarity.

The Cipher Brief: Are conspiracy theories really more prevalent now than in the past?

Davidson: I was in the Middle East in the early 2000s, and everything was a conspiracy theory. I mean, the one thing for sure was the official story was not true in Iraq or Syria. That’s the one truth you have. And it gives this fertile ground for conspiracies.

But I think it goes deeper than that. The human animal is a storytelling, story-shaping narrative animal. It’s really kind of amazing when you think about how much of our life is in the creation and consumption of narratives, taking weird facts and putting them into some kind of narrative sense. There’s no culture that doesn’t have myths, but also just rumors and personal stories. That is how our brains understand how to make sense of a whole bunch of disparate things. We want a story even if the story isn’t true.

But I think what we are seeing now with social media and a more aggressive Russia and probably China, and that kind of purposeful weaponization, it does seem like we’re at the high point of the deliberate and almost scientific engineering of conspiracies and expansion of conspiracies. That does feel different than myths from ancient Mesopotamia.

O’Shea: I think conspiracy theories tell us more about those who want to believe them and embrace them despite the obvious lack of reality. Back when Texas seceded from the union in 1860, it had its declaration. And in that, one of the main reasons, besides slavery, was a conspiracy theory which had absolutely no value to it, no evidence at all. In their declaration of why they were leaving the union, it said that the northerners were shipping poison to African slaves to kill their masters and were sending seditious letters. There is zero evidence of this. And yet the population was so worried about this, and talked themselves into a frenzy, that there was this widespread, either belief in it, or sense that they wanted to feel aggrieved. So part of the secession from the union was based on conspiracy theories. There’s a long history of that in the United States.

Sipher: I was reading this morning in the sports page, an injured athlete wrote something about “everything happens for a reason” when he explained his injury. Frankly, it’s probably more likely that things don’t happen for a reason and that we have limited control over the events that impact our lives, so we need to create stories. We need to take disconnected facts, create narratives and stories to understand our world. And at the same time, we also want to be the center of those stories. And we feel even better If, in fact, as we put that narrative together, we’re the heroes of the story that have uncovered some sort of injustice.

If you can create a conspiracy that puts something out there that can’t really be proven or disproven and you hit it over and over again, it’s probably more successful as a weapon than one that is really detailed.

And we’re seeing bad actors, bad foreign actors, for example, being really successful at this — the Russians, the Chinese, and others — whereas in the past, they might’ve had to create a fake story and pump it into our media landscape. Nowadays, they can use social media, they can look for craziness and bad actors and how our tribal nature has us attacking each other and they can just exploit that and amplify those kinds of things.

There was a story yesterday in the paper about how the Russians are pumping stories related to the (U.S.) southern border. And I’m sure they didn’t have to create that. They saw us fighting each other on it, and they said, Well, that’s great, if Americans are attacking each other, all we have to do is amplify that.

The Cipher Brief: Adam, are there examples of conspiracy theories that have had national security impact or real political impact overseas, almost like an undertow that you wouldn’t have seen otherwise?

Davidson: My mind immediately goes to Iraq. I was there (in 2003). I was in the south, and then I got to Baghdad a couple days after the statue fell and the regime crumbled. I don’t have exact numbers, but I’d say a significant plurality of Iraqis were on the fence about the Americans. They were open to, and also willing to not be open to, an American occupation and the American presence. The way in which the question about who these Americans were was explored entirely through conspiracy theories.

It also made me realize, I don’t think it’s that Americans happen to not like conspiracy theories. It now turns out we do like them an awful lot. But until not that long ago, we did have at least widely recognized gatekeepers of the truth. I grew up as a Walter Cronkite kid. We had these people — our dads and our ministers or rabbis and these voices, these gatekeepers that were trusted and seen. And obviously that has collapsed in the U.S. to a great degree. But in a lot of countries, that has never existed. There’s never been a tradition of “Oh, I trust them because I have a sense that they are going to be straight with me.” And in places where that can’t possibly exist, how else is information going to spread, except through the more colorful story, the simpler story that can really move a lot of people? That’s the story that’s going to spread.

The Cipher Brief: How much does the clickbait phenomenon have to do with spreading conspiracy theories? How responsible is the journalistic profession and the commercial end of that in terms of its proliferation?

Davidson: I would say a hundred percent. Or close. I think journalists are still trying to struggle to figure out what our role is in this environment and finding that it turns out we didn’t all have agreement on responsible reporting practice. It just never was on the table as much. I think at “elite” media — if I can obnoxiously call the places I’ve worked “elite,” like The New York Times magazine, the New Yorker and NPR — the direct clickbait, article by article, isn’t a real factor. I’ve never been told how one or another article performed.

But there is a general higher-level analysis – these topics do well, these areas do well. Now we really know that foreign coverage just doesn’t pay the bills. It’s really expensive to have a foreign bureau, and that is a loss. Responsible news outlets are still doing it, but not nearly as much. And so to my mind, journalists are not contributing directly to conspiracy theories, but they’re already weak and they’re weakening in their ability to be counterweights to the most deranged, or even the least deranged, just any of the conspiracies.

The Cipher Brief: One of the features of enduring conspiracy theories is how sticky they are. They persist for a long time, even in the face of overwhelming, factual, countervailing evidence. Why do some conspiracies remain sticky – Elvis is still alive, moon landing hoax, et cetera?

O’Shea: Stickiness – that’s a really good word. I think by and large, they authenticate your own prejudices.

One of the oldest conspiracy theories is the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, about a small group of Jews back in tsarist Russia that want to rule the world. It’s a clear forgery put out by the tsarist Okhrana, their security service, to basically justify pogroms and murders against their own Jewish citizens. I think they’re “sticky” because they reflect and undergird people’s prejudices, A. And B, they’re really simple stories.

Life is genuinely very complex. As CIA officers, we dealt in that complexity and we were very comfortable with ambiguity, not knowing the answer, trying to figure out the complexity. But I think most people in their lives, they just want a simple solution. Who is responsible? Who did this to me? Not only do they want to be heroes in their own narrative, they also are victims of their own narrative, right? It can’t be my fault, this didn’t occur.

I think that the stickiness comes from technology, and it comes from what people already believe and are looking for reasons to believe.

Sipher: Obviously conspiracies that benefit you or your party or your country can get into this feedback loop where it’s clear that the conspiracy theory is probably not true. And likely when they started the conspiracy theory, they also understood it wasn’t true. But they’ve been saying it for so long and it’s been coming back to them that I think these people start to believe it.

A good example in the United States is this one we’re seeing about the “deep state.” We all worked for 30-plus years inside the intelligence community. We saw ourselves as public servants. We were focused on a mission. There was no partisan anything. I mean, I didn’t know what party any of you guys were.

But nowadays, there’s this view in parts of the country that there’s a deep state that’s working against whoever happens to be president, or against the party. If a senior official wants something, the FBI, the Justice Department, the CIA and others are working against them in some ways.

And that’s quite dangerous, if that view is put out there. Maybe it was put out there originally for cynical reasons – they said my policy is not getting implemented, therefore it must be someone working against me, it must be the FBI or the Justice Department or CIA. That cynicism gets into the system. It starts to be part of the party, people who get elected, they get elected on saying the same thing. And before long, there’s a huge narrative in the country that there’s a deep state and there’s people who truly believe it and are actually sometimes willing to commit violence because they believe it so strongly when it was never true.

The Cipher Brief: You guys will recall the conspiracy theory that came out that the CIA was distributing cocaine in neighborhoods of Los Angeles to earn money to fund the Contra program against the regime in Nicaragua in the 1980s. Those of us working inside saw it for the absurdity that it was, but it was very sticky and had real resonance across different parts of the political spectrum, each using it for their own political means. And there were elements of it that someone could point to as true – yes, the CIA was supporting the Contras against the regime in Nicaragua. So there’s usually some element of truth they can point to.

Davidson: You remind me of something that seems to really work with conspiracy: having some specific detail. I remember in Iraq, there was a big conspiracy among a lot of Iraqis that Saddam Hussein and George W. Bush planned the war together, and that Saddam was now living in the White House. And I used to always say, Let’s just say all of that is true. Why would they put him in the White House? Why wouldn’t they put him on some islands somewhere? But it’s having the one thing that you can hang on to.

My brother-in-law runs the international foundation for electoral systems that helps elections all over the world. And what he’s seeing everywhere, and even more so in these countries that don’t have anything like our media system, is it’s all targeted conspiracy theory, disinformation campaigns, and that it’s really hard to think of any way to combat them. It’s got to be a major issue.

O’Shea: When facts don’t count, when it’s nihilism, that is not just a step – that is a huge leap towards totalitarianism. You know what “facts” were under Stalinism. Facts were what the leader says. And so when you start questioning basic facts like who gets the most votes, when you don’t accept the outcome of elections, then how do you settle elections? Either through violence or through a leader just saying it’s so. And that’s really dangerous, when the state gets to decide what the facts are, rather than experts in the messy process of figuring out what facts are, and the disparagement of expertise.

Sipher: The ones that concern me are the ones that are affecting our politics. Now we see that Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. might have Aaron Rodgers come on as his vice president, and the two guys are conspiracists, anti-vax people and all these kinds of things, which is crazy. They’re not going to win, but they could very much impact our elections one way or the other.

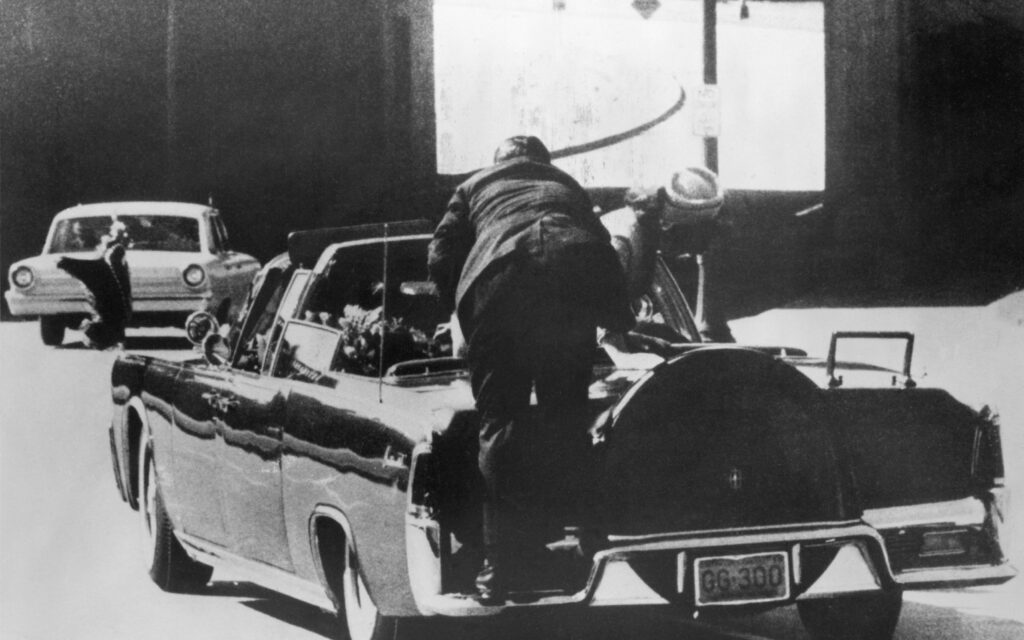

The most important ones are the ones that were really good at using deception, disinformation, agitation, and assassinations to all feed off of each other, to create narratives to try to fool people into what they’re doing. We saw it in the CIA, when we were trying to investigate inside the CIA for potential moles, potential spies inside. The Russians were very effective at creating a worldwide deception campaign to try to give us all sorts of other reasons other than the fact that Robert Hanssen or Aldrich Ames or others were spying inside the CIA. And so these things all have great import and therefore it’s important to understand how conspiracy theories are put together.

But I guess a fun one, there was a story — a true story — that several Russian tourists in Egypt, at Sharm-el-Sheik at the beach, were bitten by sharks. It was affecting the tourist industry. People weren’t going to Sharm el-Sheik, they weren’t going into the water, and therefore the Egyptian tourist industry was suffering.

A senior Egyptian official made a comment publicly that the Israelis were training sharks or perhaps even using robot sharks to impact the Egyptian tourist industry to try to hurt Egypt. And the notion that perhaps the Mossad was training sharks, and maybe even training them to go after Russians specifically – all of it’s crazy, but you realize if one person says something like Oh, these sharks must’ve been sent here, then it creates this whole world and people follow on it. And before you know it, it’s a theory.

Davidson: I do love that one. Then there’s the “chemtrails.” There are people who say that airplanes are pouring chemicals to make us all neutered so that we won’t have children. But then there’s others saying the airplanes are pouring chemicals to make us all oversexed, and so that we won’t fight against the government. That they’re making us crazed, so we’ll fight each other. Another one is that they’re poisoning our food because rich people have these secret farms under the ground that are safe and we’re all going to die. And you can look around – most people aren’t dying from poison.

But you start almost – I don’t know if admire is the word, but you start seeing these conspiracies and which ones really have legs that really are adaptable. They’re good for any purpose.

O’Shea: In 1857, the British Empire in India came very close to failing when dueling conspiracy theories smashed into the British Empire. The British Indian army that was there, they introduced a new cartridge for their rifles. And to use it, you had to bite off the end of the cartridge and pour in the black powder to get the musket ball to fire. And the British aren’t stupid, and they’re like, Oh, we’ve got Muslims and we’ve got Hindus, so we’re going to use vegetable oil to oil the cartridges.

Well, dueling conspiracy theories started in India. The first, on the Muslim side, that the British were using pork fat, which would then destroy their religion. And the Hindus figured it was made of cow fat to take away their caste. And the two sides, the Hindu soldiers and the Muslim soldiers, they combined together, even though their dueling conspiracy theories were diametrically opposed.

This allowed them to revolt against the British who were like, No, really, it’s vegetable oil! Why would we do this? And yet, the British Empire almost crumbled because of these conspiracy theories. And the British had all sorts of studies, and even to this day, they still don’t know why these conspiracy theories arose. I think this was probably the bottom line: we don’t want the British here. So they had to come up with a conspiracy theory to do that.

The difference now is technology, and our own polarization of politics, which makes it more dangerous even than the British Empire.

The Cipher Brief: What that story tells me is that they really do fill a need. There’s either a psychological or a political or a need for that theory. It doesn’t matter how absurd the theory was.

Sipher: In general, I think people just refuse to believe that life is random, and therefore they have to create answers to questions, because the world’s complex. You can imagine that with organized religion, back when we couldn’t explain why the sun came up every day or why certain things happened, you had to create stories to fill those needs.

The Cipher Brief: Is there utility in trying to combat conspiracy theories? Can you play whack-a-mole against them? What’s the role of media in combating them?

Davidson: Under Saddam Hussein, there was only Saddam’s regime, and after he fell, there was this period of a year or two where there was a really open media environment. There was nobody really paying attention. There was something like 200 newspapers started in Iraq.

I went to the offices of one, and the publisher was talking about how great it is – “We have freedom now. We have freedom of speech, freedom of press.” And I said, “But your paper is just conspiracy theories.” Literally every article was a different conspiracy. And a lot of them contradicted each other. And he said, yes, that is freedom. We print all the conspiracy theories and the reader can decide.

So first off, I can’t say no, the media has no role, or for that matter, intelligence has no role. This is the challenge of our time. Whether it’s national security, whether it’s climate change, there’s this idea of the tyranny of the minority, that small groups of people are able to influence large groups of people. Jerry’s India story made me think, they were going to be against the British being there anyway, the Iraqis were going to be against the Americans occupying Iraq no matter what. So there’s conspiracies that support what was already a prevailing view.

But then as we’ve seen in our country, there are conspiracies that shift people. There’s no obvious reason why there would be a strong pro-Putin GOP alliance. That, in my mind – and maybe I’m the conspiracy theorist now – but that is highly likely the result of a targeted campaign. And that obviously is the fear, that people are suddenly going to be actively supporting things they don’t like, which they have no reason to, which kind of gets to the core of democracy.

So on the one hand, I’m not ready to say the media has no role. We have a huge role. On the other hand, I don’t know what our role is, because there’s evidence that directly factually countering them reinforces the belief in them.

We definitely need to come up with something. It’s a major risk and a major challenge.

The Cipher Brief: John, you’re put in charge of the program to counter conspiracy theories that maligned states are using to undermine our security. What do you do?

Sipher: Fighting trolls is probably not the way to do it. But I get on Twitter and I like fighting with idiots, and I probably make things worse. That’s how the algorithm works. It realizes that you get angry, and so it wants to hype that up.

What do I do to stop Russian disinformation? I would give maximum amounts of weapons and support to Ukraine so that Russia loses and Putin goes out of business. We actually have to humiliate and destroy the Russian military and hope their intelligence services fall apart because almost every Russian spy and defector we’ve ever had realized that it was the security services that is the evil that supports that system. And the only way to beat it is to destroy it. And that’s not going to be easy. But I think that’s the way to go.

O’Shea: Ultimately, when societies deal with truth and facts, whatever they are, however messy they are, they tend to be more successful. Stalin’s Russia for the Russians was a horrific place to live, because they couldn’t speak the truth. They couldn’t communicate and argue, and scientists couldn’t come up with real answers. People died because they came up with fake information.

So bad information makes for bad societies. And at the end of the day, the most successful societies are going to be the ones that adhere most closely to the truth and adhere least of all to conspiracy theories. And I’m hoping that in the U.S., we stay the course and deal with what’s true and try to figure that out as opposed to saying, I already know what’s true. I’m just going to look for facts to make it so.

O’Shea: I would just say, Get involved. Staying silent, even at Thanksgiving dinner, your nutty uncle starts talking about some conspiracy theory, the deep state this or that. If you stay silent, you have a nicer Thanksgiving dinner, but you’re allowing this to spread and you’re allowing this to grow. Become politically active, certainly vote, but inform yourself and push back and have these tough conversations with people who throw these things out there as they often do when you’re at a party.

Sipher: I worry that we’re getting more and more people into our political system in Congress who are conspiracy theorists, who are extremists, who believe this crazy stuff, either because it benefits them for partisan reasons or financial reasons, or they’re just nut jobs. And good intelligence, as we all know, requires good serious oversight. Government is serious business for serious people. And the people in the CIA take their mission to protect Americans pretty seriously.

In the days before we had good oversight, the CIA sometimes lost its way and the Executive Branch lost its way. And so I worry that if the CIA is going to Congress to talk to them about what they’re doing, what their needs are, what’s important, and they have people there who actually believe this stuff about the deep state or what have you, I think it really can hurt us seriously in the intelligence community. And so I worry about our domestic politics.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief

Related Articles

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — Russia’s reaction to the new infusion of U.S. aid for Ukraine has ranged from shrugs to fury, from warnings of nuclear […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — When Chinese President Xi Jinping came to San Francisco last November to meet with President Joe Biden, Chinese pro-democracy activists in […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — Ukrainians greeted Saturday’s long-awaited House passage of $60.8 billion in aid with justifiable jubilation. For months, their soldiers, civilians, and political […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — A race for control of space is underway, and just as on earth, the U.S. and China are the top competitors. […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — For nearly a week, the Middle East and much of the world were on a knife’s edge, waiting for a promised […] More

BOTTOM LINE UP FRONT – Less than one week after Iran’s attack against Israel, Israel struck Iran early on Friday, hitting a military air base […] More

Search